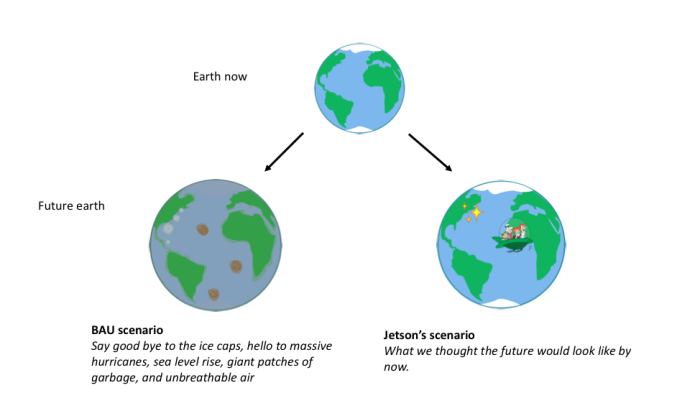

After working in climate change mitigation, I find that my vision for the future flips between two different scenarios:

Given the frustration of the political system and the apparent lack of progress in this domain, it can be hard to believe a Jetson’s scenario is even a possibility.

However, from time to time I hear about projects, actions, and successes that make me believe the Jetson’s scenario is not only possible but inevitable. And then my despair turns into excitement.

In November of 2017, I met someone who refreshed my belief in this scenario – Brian Boserup. Brian and I both attended a clean shipping conference hosted by the Danish Eco Council in Copenhagen. After hearing about his company, Blue Technology, we arranged to meet for further discussion before I left Denmark.

The next day, Brian and I met at Denmark’s national aquarium, Den Blå Planet, to record the interview. The perfect backdrop, said Brian, since it would represent everything we are trying to protect.

We sat in the aquarium’s restaurant, with a view looking out into the open ocean. As we talked, various school groups funneled in an out of the restaurant, while various ships funneled in and out of Copenhagen’s harbor.

Humanity is unique in that it is the only species on this planet to engage in trade. Shipping has lubricated this process significantly, by providing the most efficient way of moving goods from one geographic location to another. Because of economies of scale and lower frictional resistance on ocean compared to land, ships are at least 2.5 times more efficient than trains and 9 times more efficient than trucks at moving cargo on a tonne-mile per fuel basis.

Despite this efficiency, shipping is still a major contributor to global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, producing almost 3% of global carbon emissions – a higher contribution than Germany. As the world makes efforts to reduce the consumption of fossil fuels following the signing of the Paris Agreement, shipping will also need to address its emissions. Shipping as a sector faces the unique challenge of being truly international in scope, making it difficult to assign emissions guilt to any one country. Electricity consumed in France, for example, clearly falls under the responsibility of the French government. But if a business in the US manufactures goods in China and ships them to customers in Europe, which party is responsible for the transport emissions? The manufacturer in China? The business owner in the US? Or the customers in Europe?

Shipping emissions (along with aviation emissions) were notably left out of the Paris Agreement, with the understanding that the International Maritime Organization (IMO), the governing body charged with regulating international shipping, would formulate its own strategy to getting to zero emissions. In April of this year, the IMO finalized its initial GHG strategy: 50% reduction of 2008 emissions by 2050, with complete decarbonization by 2100. If the IMO is serious about stopping GHG emissions from ships, shipowners, operators, and builders will soon need to reconsider the design of ocean going vessels.

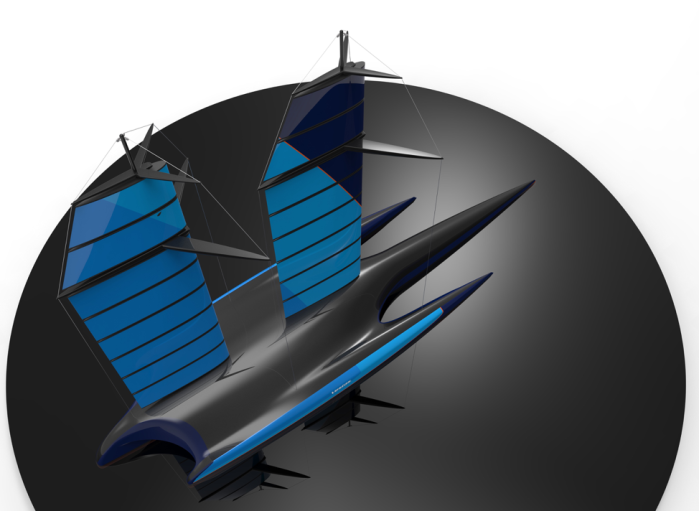

Brian began thinking about this problem ten years ago, when he decided to design a truly zero emission vessel. For the past decade, he has been working with experts in the marine sector to complete the plans for this vessel — aptly called the Liberty.

The Design

Blue Technology designed the Liberty to maximize wind harvest, minimize frictional resistance from the air and sea, and eliminate the use of ballast water for stability. The result: a carbon fiber trimaran design emblematic of the sailboats competing in America’s Cup.

One of shipping’s major costs is fuel – it takes an enormous amount of energy to push weight through water. Conventional shipping expends fuel not only on moving onboard cargo, but on moving both the weight of the ship and its ballast water. Brian estimates that 30% of a ship’s fuel consumption is spent on moving ballast water alone. The Liberty’s carbon fiber body is much lighter than traditional steel, reducing the weight of the ship and thereby increasing its fuel efficiency. Its trimaran hull maintains a shallow draught of about 4.5 m (traditional container ships have a 10-16 m draught), allowing it to service almost any coastline and giving every costal community cheap access to global trade.

The Propulsion System

The main power source of the Liberty is the wind. The average wind speed on the world’s oceans is around 7 m/s, which provides enough power for this ship to reach speeds of 18-22 knots. Since wind force is proportional to the cube of wind speed, wind speeds of 14 m/s increase the power output by a factor of eight. Traditionally, winds of this speed cannot be harnessed by sailboats due to stability concerns. The Liberty’s 55-meter wide trimaran hull, however, provides enough stability for the Liberty to safely operate even at very high windspeeds.

The wind energy is harvested from two 110 m high wing sails (think of two vertical airplane wings). The wing sail is divided into eight independent units, which can each rotate 360-degrees around the mast. The masts are supported by three stays, allowing this technology to perform in even the strongest wind conditions.

The secondary power source is electrical energy generated from four propellers that are deployed to generate electricity when wind speeds exceed 8 m/s. An additional 15,000 m2 of exterior solar cells produce electricity that is stored in onboard lithium batteries. During periods of low wind speeds, the batteries provide the energy to power the ship.

The Cargo

The Liberty is a new type of ship optimized for performance and seaworthiness rather than to accommodate a specific volume of cargo. This type of hull is suitable for light weight commodities such as containers, cars or passengers.

Liberty – Container Carrier

The Liberty can contain around 1,100 containers, all held within the trimaran hull. By comparison, the largest containerships at sea today have a capacity above 20,000 containers, which are mostly stacked externally. Storing the containers below deck protects them from seawater, wind, and sun damage.

The Liberty has an onboard container handling system, which can line up the containers for next destination close to the unloading hatch. Once moored, it lands two reach stackers, which can load/unload the containers with the same efficiency of 3-5 of the most modern cranes. With this system the Liberty is completely independent of any port equipment. This minimizes the time spent onloading and offloading at port, reducing overall costs to the ship operator and allows the Liberty to visit virtually any community accessible by water.

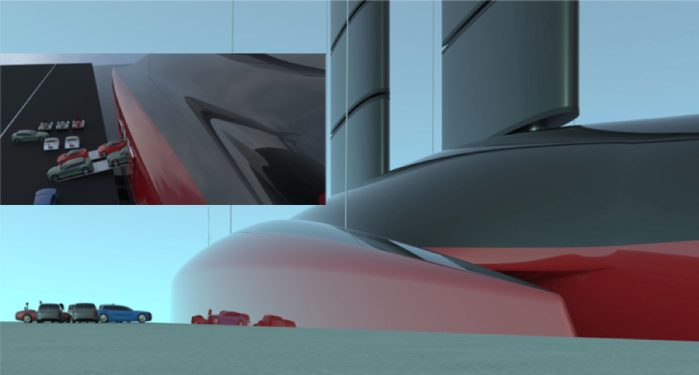

Liberty – Pure Car Carrier

Alternatively, the Liberty can be configured to operate as a pure car carrier, with the capacity to accommodate 2,000 cars. Boserup plans to approach automanufacturers that produce electric vehicles so that the transport of their cars is as environmentally responsible as driving them.

The People Behind the Liberty

It has been a 10-year development journey for Brian Boserup, who has had assistance from Lars Roug (3D-Illustrater) to visualize the concept. Naval architects, universities, and a number of seafarers and other stakeholders have contributed to mature the original ideas.

Blue Technology is now advised by a board representing major players across the shipping industry, including Henrick O. Madsen, the former president and CEO of DNV-GL, Lars Robert Pedersen, the Deputy Secretary General of BIMCO, Niels Bjørn Mortensen, a former director from Maersk, Sofia Fürstenberg, the Business Development Manager for Nor-Shipping, Søren Vinther Hansen, the COO of Vessel Performance Solutions, and Hans Otto Kristensen, a leading naval architect and environmental consultant for the shipping industry.

Next Steps

Blue Technology plans to optimize its technologies during 2019, complete the blueprint by 2020 and build the vessel by 2024, making zero emission transport possible in six years.

Keeping Focus

Given today’s political climate, it can be frustrating and challenging to promote a new technology that competes with the incumbent steel, oil, and shipping industry. I asked Brian what he does to maintain focus during periods of uncertainty or frustration.

“When I have doubt, I meditate to calm down and regain focus. My motivation is my love of the ocean, and my worries for the consequences of climate change. We are heading towards a difficult time where millions of innocent people with a minimal carbon foot print, if any, will be killed as the direct result of the overconsumption of others. I am living in one of the countries with the highest CO2 emissions per capita and I feel obligated to reduce the impact of climate change, as I doubt that Tesla and Amazon are going to give us all a free ticket to Mars. I have witnessed the deadly power of nature, which is why I will continue this journey until the end. The ships of the future will not suddenly emerge, they need to be developed, and we invite everyone with the interest of joining this adventure to come along.”

You can follow the progress of the Liberty at www.bluetechnology.dk